Osteoporosis and osteoporotic

vertebral compression fractures are commonly encountered clinical

problems. The definition of osteoporosis is diminished bone density

measuring 2.5 standard deviations below the average bone density of

healthy, 25-year-old, same-sex members of the population. In the United

States, approximately 35% of women older than 65 years have

osteoporosis.

Vertebral compression fracture (seen in the image below) is the most common complication of osteoporosis. More than 700,000 new vertebral compression fractures occur every year in the United States alone, accounting for more than 100,000 hospital admissions and resulting in close to $1.5 billion in annual costs.

Go to for more complete information on this topic.

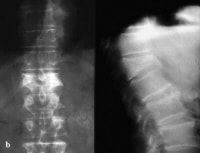

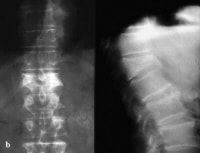

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of an L1 osteoporotic wedge compression fracture. Most

of patients experiencing an osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture

remain asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic; however, a large number

of these patients do experience significant pain, resulting in decreased

quality of life and disability. Conventional medical treatment for

these patients includes pain medication, activity limitation, physical

therapy, and (possibly) bracing.[1, 2]

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of an L1 osteoporotic wedge compression fracture. Most

of patients experiencing an osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture

remain asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic; however, a large number

of these patients do experience significant pain, resulting in decreased

quality of life and disability. Conventional medical treatment for

these patients includes pain medication, activity limitation, physical

therapy, and (possibly) bracing.[1, 2]

Patients with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures are usually treated nonoperatively.

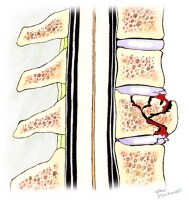

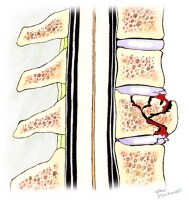

Anterior wedge compression fracture with an intact posterior vertebral cortex.

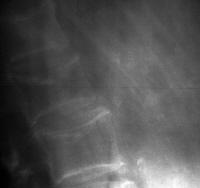

Anterior wedge compression fracture with an intact posterior vertebral cortex.  Osteoporotic spine. Note the considerable reduction in overall bone density and the lateral wedge fracture of L2. A

second common form of fracture is a central crush fracture, which

frequently occurs in the lower lumbar spine. Increased interpedicular

space, involvement of the posterior cortex, or laminar fracture suggest a

burst fracture (seen in the image below), which may be unstable.

Osteoporotic spine. Note the considerable reduction in overall bone density and the lateral wedge fracture of L2. A

second common form of fracture is a central crush fracture, which

frequently occurs in the lower lumbar spine. Increased interpedicular

space, involvement of the posterior cortex, or laminar fracture suggest a

burst fracture (seen in the image below), which may be unstable.

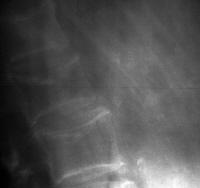

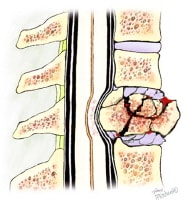

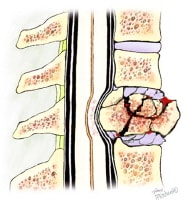

A vertebral burst fracture.

A vertebral burst fracture.

A combination of these factors, that is, decreased, asymmetrical, and irregular bone density, is a hallmark of osteoporotic bone loss. Coupled with even minimal flexion and/or axial loading, these factors predispose the osteoporotic vertebrae to wedge-shaped compression fractures, acquired kyphosis, and general height loss.

Once 1 vertebral compression fracture has occurred, a biomechanical environment is created that favors additional fractures. This occurs as a result of the vertebral compression fracture causing an additional kyphosis, shifting the patient's center of gravity anteriorly and producing a longer moment arm. This longer moment arm increases kyphotic angulation and places additional stress on the vertebrae, particularly the vertebrae adjacent to the primary fracture.

Progressive kyphosis, additional fractures, and neurologic changes are potential complications of osteoporotic compression fractures. These complications can be minimized with appropriate, expeditious care.

All vertebral compression fractures require a systematic examination to rule out an underlying systemic illness, such as malignancy, infection, or renal or liver disease.

Vertebral compression fracture (seen in the image below) is the most common complication of osteoporosis. More than 700,000 new vertebral compression fractures occur every year in the United States alone, accounting for more than 100,000 hospital admissions and resulting in close to $1.5 billion in annual costs.

Go to for more complete information on this topic.

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of an L1 osteoporotic wedge compression fracture. Most

of patients experiencing an osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture

remain asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic; however, a large number

of these patients do experience significant pain, resulting in decreased

quality of life and disability. Conventional medical treatment for

these patients includes pain medication, activity limitation, physical

therapy, and (possibly) bracing.[1, 2]

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of an L1 osteoporotic wedge compression fracture. Most

of patients experiencing an osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture

remain asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic; however, a large number

of these patients do experience significant pain, resulting in decreased

quality of life and disability. Conventional medical treatment for

these patients includes pain medication, activity limitation, physical

therapy, and (possibly) bracing.[1, 2] Patients with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures are usually treated nonoperatively.

Types of vertebral compression fractures

Vertebral compression fractures characteristically demonstrate a wedge-shaped pattern (seen in the images below) with gross collapse of the anterior portion of the vertebral body and relative preservation of the posterior body height. Anterior wedge compression fracture with an intact posterior vertebral cortex.

Anterior wedge compression fracture with an intact posterior vertebral cortex.  Osteoporotic spine. Note the considerable reduction in overall bone density and the lateral wedge fracture of L2. A

second common form of fracture is a central crush fracture, which

frequently occurs in the lower lumbar spine. Increased interpedicular

space, involvement of the posterior cortex, or laminar fracture suggest a

burst fracture (seen in the image below), which may be unstable.

Osteoporotic spine. Note the considerable reduction in overall bone density and the lateral wedge fracture of L2. A

second common form of fracture is a central crush fracture, which

frequently occurs in the lower lumbar spine. Increased interpedicular

space, involvement of the posterior cortex, or laminar fracture suggest a

burst fracture (seen in the image below), which may be unstable. A vertebral burst fracture.

A vertebral burst fracture. Etiology of osteoporotic compression fractures

Cortical and trabecular bone loss, as well as disruption of the microarchitecture of bone, are all typical of osteoporosis. Spinal flexion and axial compression have been shown to place maximal stress on the superior endplate of the vertebral body. The asymmetry of the vertebral body produces maximal stress at the anterior aspect of the cortical shell.A combination of these factors, that is, decreased, asymmetrical, and irregular bone density, is a hallmark of osteoporotic bone loss. Coupled with even minimal flexion and/or axial loading, these factors predispose the osteoporotic vertebrae to wedge-shaped compression fractures, acquired kyphosis, and general height loss.

Once 1 vertebral compression fracture has occurred, a biomechanical environment is created that favors additional fractures. This occurs as a result of the vertebral compression fracture causing an additional kyphosis, shifting the patient's center of gravity anteriorly and producing a longer moment arm. This longer moment arm increases kyphotic angulation and places additional stress on the vertebrae, particularly the vertebrae adjacent to the primary fracture.

Progressive kyphosis, additional fractures, and neurologic changes are potential complications of osteoporotic compression fractures. These complications can be minimized with appropriate, expeditious care.

All vertebral compression fractures require a systematic examination to rule out an underlying systemic illness, such as malignancy, infection, or renal or liver disease.

No comments :

Post a Comment